Interview with Nick Mason of Pink Floyd

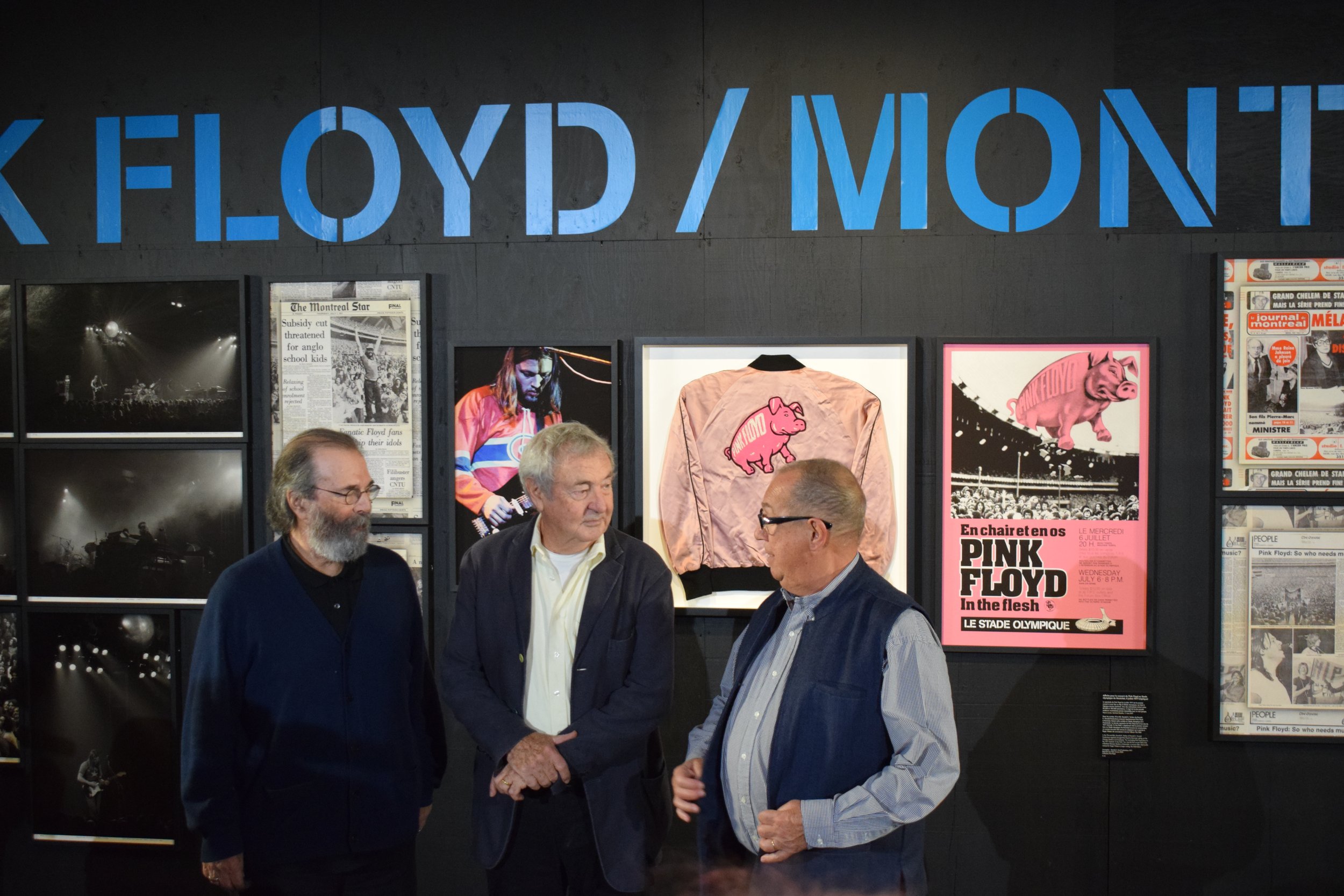

Michael Cohl, Nick Mason, and Aubrey Powell at the premier of Their Mortal Remains in Montreal on November 3, 2022.

In classic rock lore, the pantheon of legendary English drummers is an exclusive group of six icons. Although fans will endlessly quibble about who was the “best” drummer, Pink Floyd’s Nick Mason is in select company along with Ringo Starr, Keith Moon, Charlie Watts, John Bonham, and Ginger Baker. Each of these drummers contributed to their group’s success through their unique style, which imitators and admirers have sought to replicate for the past fifty years. Today only Nick Mason and Ringo Starr are still with us, and thankfully neither of them are showing any signs of slowing down.

Nick Mason has been the steady beat of Pink Floyd since 1965 and is the only band member to appear on every album in Pink Floyd’s storied discography. More than a drummer, Mason co-wrote several Pink Floyd compositions, including “One of These Days”, “Echoes”, “Time”, and “Careful With That Axe, Eugene.” In recent years, Nick Mason has been instrumental in introducing Pink Floyd’s repertoire to younger audiences. In 2017, Mason worked alongside Aubrey ‘Po’ Powell of Hipgnosis to curate Their Mortal Remains: The Pink Floyd Exhibition, a retrospective exhibit on the band’s impact on art and culture that has been seen by over 500,000 people across the world. The following year, he formed a new band, Nick Mason’s Saucerful of Secrets, which continues to tour across North America and Europe performing music from Pink Floyd’s early years. The latest iteration of Their Mortal Remains opens in Montreal on November 4th, and you can read our review of it later this weekend, accompanied by several photos from the exhibition.

We spoke to Mason from his hotel room in Seattle, where the Saucerful of Secrets were closing out their North American tour. In a wide-ranging interview, we discussed the opening of the Their Mortal Remains exhibition in Montreal, the 50th anniversary of Dark Side of the Moon, and performing with the Saucerful of Secrets.

I’m very excited to be speaking with you about the Pink Floyd: Their Mortal Remains exhibition opening up in Montreal this week. What made Montreal the appropriate next city for the exhibition tour?

I suppose it’s about looking for somewhere where the audience might be receptive. I think one of the best things about Montreal is the linkage into Europe through the French connection. France was incredibly important to Pink Floyd when we started because we could play all over France and fill venues in a way we couldn’t in the UK. Certainly, for us, the Montreal show on the Saucers tour was one of the best gigs of all. I think Montreal is a really good choice. Pink Floyd played here seven times between 1971 and 1994, plus you were here a couple weeks ago with the Saucerful of Secrets.

Is there one show for you that is the most memorable?

Not particularly, but everyone always asks about Roger spitting at the crowd at Olympic Stadium in 1977. I sort of feel that night was about the disconnect between Roger and the fans, and it could have happened really anywhere on that tour. It just happened to come to a head on that particular night. My view is always to look on the positive side, because if not for that disconnect, The Wall would never have been written.

Do you recall Roger saying anything about the altercation in the immediate aftermath of the incident?

No, not really. Sometimes audiences get overly excited and they just want to shout and holler. It does feel a bit as though they’re missing the point, which is what Roger was reacting to. I don’t actually remember at what moment in the show or during which song the thing occurred… there was a lot of shouting going on. It’s a little bit vague, but that disconnect between an audience and a performer is the significant aspect that I retain from it.

Despite the spitting incident, Montrealers continued to clamour for more Pink Floyd shows, and in 1994 you played three well-received shows at the Olympic Stadium on the Division Bell tour.

Yes, those nights were terrific. I remember those shows because at the same time it was an introduction to the Cirque du Soleil, which I really knew nothing about before. At those shows we hooked up with Guy Laliberté, and forever after I think the Cirque was an influence on some of our staging. The Saucerful of Secrets show in Montreal a few weeks ago was one of our favourite shows of the tour actually, it was a great audience. I guess they learned from Roger.

Is there one piece that was particularly difficult to find for the exhibition? Or was there a lot of negotiating behind the scenes to convince people to put their possessions on display?

To be honest, I was actually astonished by how many things we were able to find for the exhibition. Initially, I didn’t think we could do the show. I had seen the David Bowie exhibit at the V&A in London, which was beautifully curated, and they had clearly looked after all the costumes and items he’d ever used. I just thought we didn’t have that sort of archive. But I’m pleased to say that I was completely wrong. All sorts of people came forward with various pieces. The most bizarre thing was that someone had the cane that was used to punish Roger when he was a schoolboy. I never in a million years would have thought someone had that, or that it could be added to the exhibit.

For yourself, are any of your drums on exhibit as well, and were those hard to give up as you’re currently on tour?

One of my favourite kits is actually in the exhibition. It’s a Ludwig kit that was hand-painted with the Hokusai Great Wave picture. Actually, I recreated that same drum kit for this tour we’re currently on. The same girl who painted the original, Katy Hepburn, who was an assistant to Terry Gilliam from Monty Python, actually did the work on the new kit which I’m playing at the moment, which was a lovely thing to do.

From an outsider’s perspective, it seems like you’re the heartbeat of the exhibition, and your book Inside Out is the most detailed portrait of the band. Did you always have a keen sense of history and the place of Pink Floyd?

I don’t think I did, it just happened by chance. I did originally keep a scrapbook for the first year or two, but I never really anticipated the longevity of the band or the interest that it would find. I guess I’m not very good at throwing things away, so I accidentally became the keeper of more stuff than anyone else.

Your father was a documentary filmmaker. Did he teach you anything about archiving or using physical material to construct a narrative?

That’s an interesting question, I never saw him as an archivist. He was very involved with telling stories, but he was quite good at going to other people to find the right archives rather than archiving himself. I learned a lot from him, but the archiving element I never really thought about. He was incredibly good at looking at old photographs and being able to say where it was and who was in the picture, but he was more interested in machinery and how and where it came and went. His specialties were cars and motorsports, and I loved that. His work gave me a great affection for cars.

I know you’re a big motorsport fan, have you ever been to the Montreal Grand Prix?

Unfortunately, I’ve never been to the Montreal race, but I’ve obviously been to a few over the years. It’s amazing how often my work has interfered with the Grand Prix.

Going back to your admiration for the David Bowie exhibit, are there any other bands that you’d like to see an exhibition of?

I think the most interesting would be a Beatles exhibition because they are such an important part of the rock music story. The Bowie exhibition was fantastic because that laid down a blueprint for what can be done with this sort of thing. These exhibitions are best suited to bands that have a lot of sets, costumes, or other elements of theatre. The interesting thing about our exhibition is how it goes far beyond the four people on stage. It’s really all about the other contributors who made Pink Floyd successful, like Hipgnosis, Mark Fisher, and the costume designers. The recording equipment on display is special as well because Abbey Road was quite advanced at that time. It truly was the most advanced recording studio in the 1960’s.

Speaking of that studio, we’re now four months away from the 50th anniversary of the release of Dark Side of the Moon. All these years later, teenagers are still being inspired by it and the album artwork is featured on t-shirts across the globe. What does it mean to you for that record to have this longevity that very few pieces of music have been able to accomplish?

I think it’s still really interesting that it does have that longevity. I think the important thing is to recognize that there’s not just one thing that’s responsible for the album’s lasting quality. Funnily enough, I saw Allan Parsons the other night, and he played a major part in its success with his engineering, and Chris Thomas played a large part with mixing. Roger’s lyrics were particularly relevant and still are relevant today to both 60-year-olds and younger people. All those things are powered into one album.

I’ve always been blown away by how much great music came out in 1973. In addition to Dark Side of the Moon, 1973 was also the year of Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, Quadrophenia, Band on the Run, Innervisions, Aladdin Sane, and Let’s Get It On. Each of these albums went on in some way or another to influence the next 50 years of music in their respective genres. What do you think it was about that year that led to so many impactful records?

It’s probably that 1973 marked the pinnacle of all the new music and ideas that came out throughout the 1960s. At some point after that, it imploded on itself and punk took over. 1973 was a time of so many great bands, like Traffic, Led Zeppelin, and the best of The Who’s albums were around that period. I don’t think it’s something that was in the water, I think that phases of music have a finite time to develop and build to a point after which they’ve done all that they can. After that, a young audience will then move on and create something that resonates more with them, like we saw with the Sex Pistols and The Clash. The transition into punk is fascinating really, everyone sort of wanted to move on to something a lot simpler.

How did you approach that phase of your career when the punk bands started to steal the spotlight from the groups of the early 70s?

I think we were interested in the music they were making. I certainly felt that prog-rock had reached its pinnacle; it was becoming a bit absurd with more and more elaborate sets. Prog-rock drum kits spread ever bigger and always had to be mounted on very expensive carpets. It was an era where the carpet was quite often more valuable than the drum kit itself.

This week you’ll be finishing your North American Saucerful of Secrets tour. The songs that you are playing harken back to a period that many fans aren’t as familiar with. As you look back to that catalogue, do you have an appreciation for any of those songs that you didn’t have before?

Lee Harris, our guitar player, came up with this idea of doing something that’s not another tribute band, and not just another version of “Comfortably Numb.” The Syd Barrett catalogue is far less familiar to North American audiences than European ones. So much of the USA believes that Pink Floyd started with Dark Side of the Moon. One of the things that means is that we’re not expected to have to slavishly play everything exactly like how it was done on the records. I like coming off stage having experimented a bit, that’s the spirit with which we played the music in 1967. I’m very fond of the exhibition, but seeing what we had achieved also reminded me that what I really wanted to do was get back out in front of audiences and play the drums again.